1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

The question of cladding

Research project2018

Material conscience

It is from their superficiality where we get an understanding of the materials that surround us. Their surfaces move us by evoking previous feelings and experiences. We can know their weight, we can feel their temperature, we can know their age. But besides this phenomenological understanding they also transmit to us an intellectual one. If they are human made, we can read the techniques and the thoughts of the people that shaped them, the traces of themselves in inanimate things.

![]()

Joseph Olbrich, The Secession Building,

Vienna, Austria, 1897

Vienna, Austria, 1897

The human capacity to modify the surface of things changes the understanding of the things themselves and expands their own reality. The surface can tell the story of a shape or a material, but it can also modify its logics. It can add new layers and qualities can be moved and transplanted. We are curious about these procedures that widen the meanings of the material by working on its surface. We will be looking carefully at them to investigate their grammar of traces and to understand how they generate meanings.

![]()

Facade of Saint Mark’s Basilica in Venice

The composite facade

The facades of contemporary buildings are almost without exception multi-layered. One could argue that historically this was of course always the case and that the idea of monolithic architecture is a fiction. After all interiors were always lined with more domestic surfaces and the facades of the churches we admire clad with marble. Yet today we witness an unprecedented separation of a facade’s components, each delegated its unique specialist function: from membranes for moisture control and insulation for heat retaining, to structure for load bearing and cladding for representation.

![]()

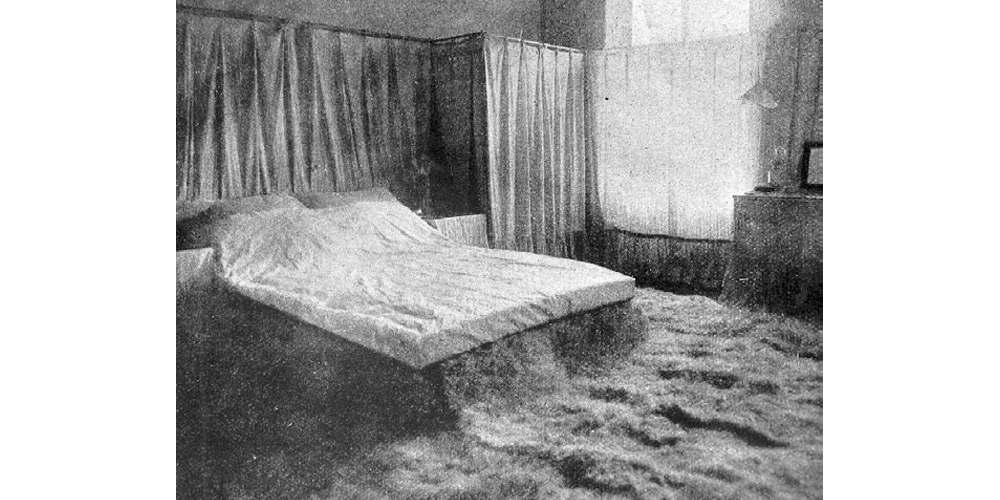

Adolf Loos, Lina’s bedroom, Vienna 1903

In his text ‘The Principle of Cladding’ Adolf Loos describes two types of architects. The first type does not imagine spaces but sections of walls. Only that which is left over around the walls then forms the rooms. The second type first imagines the intended effect of a space, which is then produced by the form of the space and most importantly its surfaces. We consider ourselves to form part of the latter and take Loos’ writing as a reminder to above all focus on the surface of things and explore the representational potential of cladding.

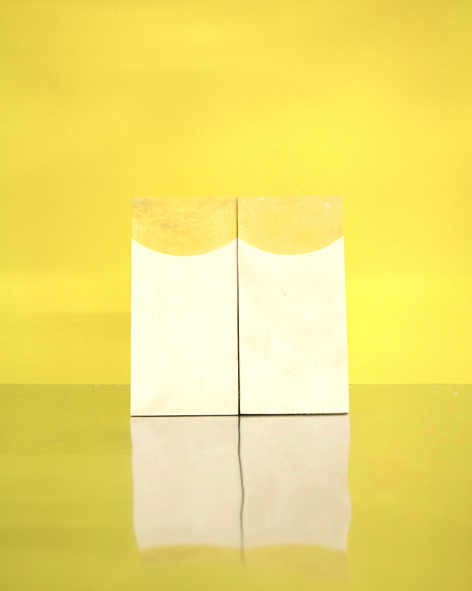

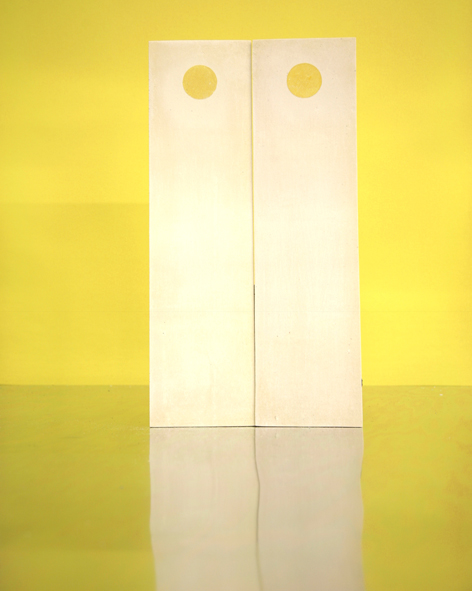

![]() Table - Tablecloth, Structure - Cladding

Table - Tablecloth, Structure - Cladding

Freedom

By not taking part in the structural system of a building, cladding must be thought of as an open work. It is an element for design and thought that offers a great deal of freedom to the architect. These liberties go further than choosing a certain material for its specific textural qualities. How humans alter a material and change its surface can give new meanings to a material. The surface has the capacity to absorb technological and cultural values. It is here, in the notion of the surface as a container of ideas, where the true freedom to architects lies.

Gunnar Asplund, Public Library, Stockholm, 1955

Gunnar Asplund, Public Library, Stockholm, 1955

Experimentation and improvisation

Yet in an increasingly standardised construction industry architects are not fully taking advantage of this freedom. We become bound to a ‘catalogue’ architecture of off-the-shelf products. As a reaction to this standardisation we explore ways of inviting chance and experimentation in the way we make things.

![]()

Jean Arp, According to the Laws of Chance, 1933

In his painting ‘According to the Laws of Chance’ Jean Arp incorporates chance within artistic production by dropping painted pieces of paper onto a surface. Should we not also value more the unpredictable nature of experimenting - with all of the randomness and chance at play? By pouring, scraping, waxing and sanding we establish an intimate and direct relationship with the materials we use. The unpredictable nature of casting and pouring leads to unplanned moments that often make for accidental and surprising results.

![]()

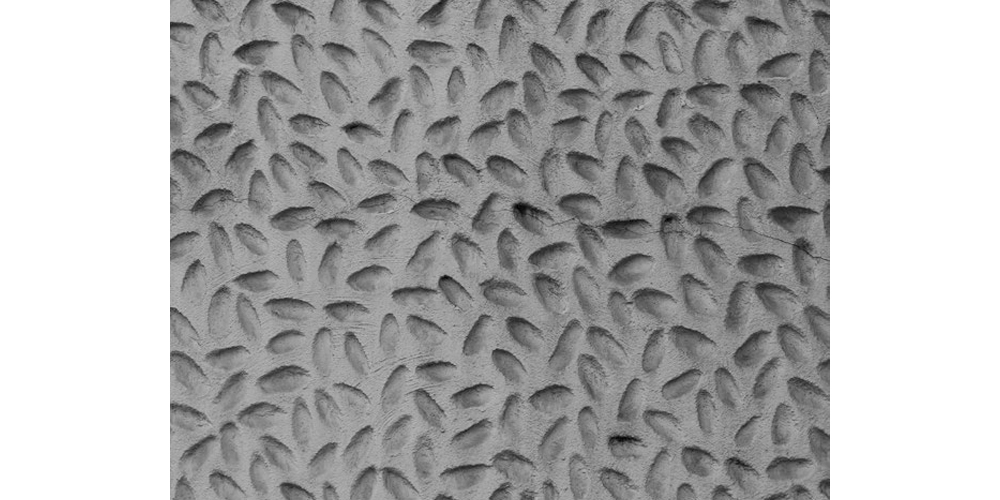

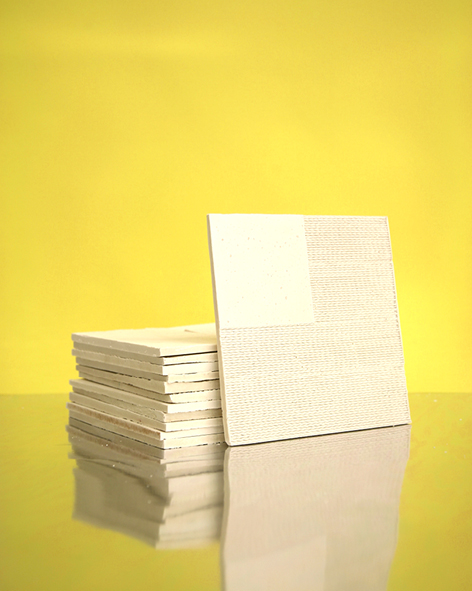

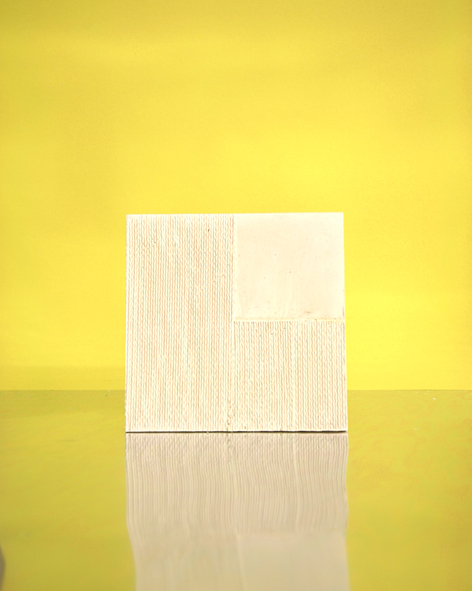

Crossover tile made during a workshop in Antwerp

Thinking through making

By focusing on the act of making we obtain a more materialistic engagement and a fuller understanding of the process by which people produce things. In the same way Richard Sennet points out in his book the craftsman that ‘we can achieve a more humane material life, if only we better understand the making of things.’ Making and consequentially thinking through making thus plays a central role in our practice. Our work, from side table to tile, is approached as a hands-on experiment and an investigates the symbolic and representational potential of the surface.

Names

01 - 06........................Crossover tile

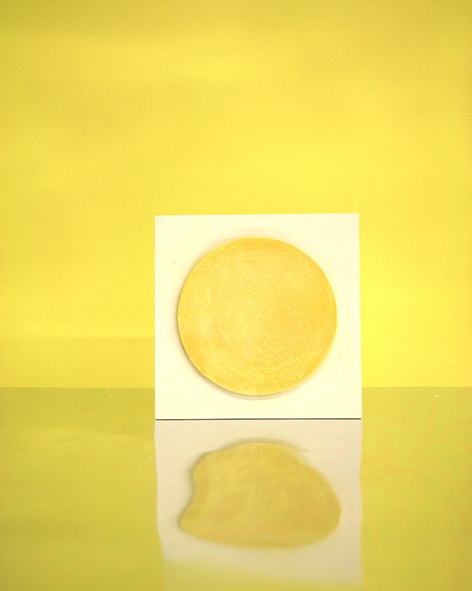

07 - 12..............................Circle tile

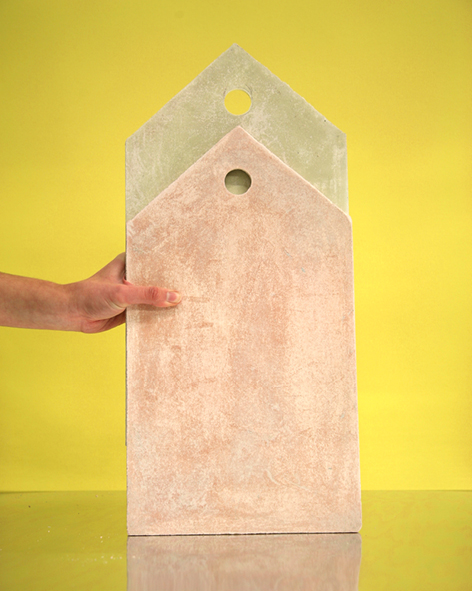

13 - 15................Overlapping shingles

16 - 18...............Polished terazzo tiles 19 - 21................Woven textured tiles

01 - 06........................Crossover tile

07 - 12..............................Circle tile

13 - 15................Overlapping shingles

16 - 18...............Polished terazzo tiles 19 - 21................Woven textured tiles

Students

Annelies Goossens

Aurélie Van Iseghem

Arno De Pauw

Fien Van den bergh

Frederik Van Kerckhoven

Isabelle Fornoville

Juliette M. P. de Bouchout

Laura Van Breuseghem

Laura Vanhoutte

Lisa Molemans

Marieke Debaere

Mattis Hoenderboom

Rupert Vanstapel

Somaie Niai

Stéphanie De Loose

Annelies Goossens

Aurélie Van Iseghem

Arno De Pauw

Fien Van den bergh

Frederik Van Kerckhoven

Isabelle Fornoville

Juliette M. P. de Bouchout

Laura Van Breuseghem

Laura Vanhoutte

Lisa Molemans

Marieke Debaere

Mattis Hoenderboom

Rupert Vanstapel

Somaie Niai

Stéphanie De Loose

February 2018

Written by A. Solanellas Teres & C. Van Noten

We do not own any of these photos. please note that all images and copyrights belong to their original owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Written by A. Solanellas Teres & C. Van Noten

We do not own any of these photos. please note that all images and copyrights belong to their original owners. No copyright infringement intended.